In recent years, a growing number of countries have reduced their holdings of U.S. dollar reserves, accelerating a trend of “de-dollarization” in 2024 and 2025. Central banks from major emerging economies to oil exporters have either sold U.S. Treasury securities or diversified into alternative assets like gold and other currencies. This article details which countries have been cutting their dollar reserves in 2025, by how much, and why – and analyzes the broader implications for global markets and the U.S. dollar’s status.

Major Reductions in U.S. Dollar Reserves

Several countries made significant reductions to their U.S. dollar reserve holdings in late 2024 and early 2025. The table below summarizes the estimated declines in USD reserves (primarily measured by net sales or drops in U.S. Treasury holdings) for key countries:

Table: Major reductions in U.S. dollar reserves by country (late 2024–early 2025). UK and Hong Kong figures largely reflect custodial holdings changes, while others are primarily central bank actions.

As shown above, Japan, the largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasuries, cut its holdings by about $27.3 billion in December 2024. China – the second-largest holder – reduced its U.S. Treasury portfolio by $9.6 billion in that month, marking the ninth month of declines in 2024. The United Kingdom (often a custodian for global investors) saw an especially sharp decline of around $44 billion in dollar holdings during late 2024, reflecting large sales or transfers of U.S. securities held via London. Major emerging economies also joined the trend: Brazil’s central bank intervened heavily in December, selling an estimated $30 billion in dollar reserves, and India’s central bank (RBI) net sold about $15.2 billion in December to shore up the rupee. In early 2025, Saudi Arabia’s dollar assets fell by over $10 billion, hinting at diversification moves or outflows, and Hong Kong’s Monetary Authority shed roughly $10.8 billion as it defended the HKD’s peg to the dollar.

Here’s the table summarizing the major reductions in U.S. dollar reserves by country from late 2024 to early 2025:

| Country | Reduction in U.S. Dollar Reserves (in billions) | Period | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | 27.3 | December 2024 | Largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasuries |

| China | 9.6 | December 2024 | Second-largest holder of U.S. Treasuries |

| United Kingdom | 44.0 | Late 2024 | Custodian for global investors |

| Brazil | 30.0 | December 2024 | Central bank intervention |

| India | 15.2 | December 2024 | Central bank intervention to shore up the rupee |

| Saudi Arabia | 10.0 | Early 2025 | Diversification moves or outflows |

| Hong Kong | 10.8 | Early 2025 | Defended the HKD’s peg to the dollar |

If you need any further assistance or modifications, feel free to let me know!

Notably, Russia had already eliminated virtually all U.S. dollar assets from its reserves by 2021 as part of a long-term de-dollarization policy. In mid-2021, Russia’s Finance Ministry announced it would completely divest the National Wealth Fund’s ~$41 billion in U.S. dollars, reallocating to euros, yuan, and gold. The Russian central bank likewise slashed the dollar’s share of its FX reserves from about 40% to just 16% between 2017 and 2021. By the time of the 2022 Ukraine war and Western sanctions, Russia’s reserves held virtually no USD, insulating it (somewhat) from the dollar freeze. This makes Russia an extreme case of reserve diversification – effectively selling off all dollar assets prior to 2025.

Why Countries Are Selling Dollar Reserves

1. Geopolitical Shifts and “De-Dollarization” Motivations: A key driver for many nations reducing dollar reserves is geopolitical risk and the perceived “weaponization” of the dollar. The use of U.S. financial sanctions – freezing central bank assets (as seen with Russia) and cutting off access to dollar financing – has prompted countries like Russia, China, and Iran to seek alternatives to holding large USD balances. Analysts note that the dollar’s “exorbitant privilege” has increasingly been used as a policy tool, especially since the 2001 terror attacks and reaching a peak with the 2022 Russia sanctions. In response, these countries fear that excessive reliance on the dollar leaves them vulnerable to U.S. policy. Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Jack Lew even cautioned that overusing dollar sanctions could drive other players away from the USD. Thus, Russia’s complete purge of dollars and China’s gradual reserve shifts are partly strategic – a hedge against being financially coerced by Washington. Beijing has openly framed de-dollarization as risk management, with Chinese analysts calling reserve diversification “routine operations” aimed at safety (e.g. buying gold instead). Similarly, countries in the BRICS bloc have voiced interest in reducing dollar dependence. For example, Brazil under President Lula has promoted using local currencies for trade within BRICS and said the bloc has the “right to discuss” alternatives to full dollar dependence. While Brazil isn’t abandoning the dollar entirely (officials stressed BRICS members **“do not intend to eliminate their dollar reserves”**), there is a clear political will to slowly shift away from automatic dollar use.

2. Diversification of Reserves (Gold and Other Currencies): Many central banks are selling some of their dollar assets to diversify their reserve portfolios. The U.S. dollar’s share of globally allocated FX reserves has fallen to multi-decade lows as central banks buy other currencies and gold. At the end of 2024, the USD comprised only 57.8% of global reserves – the lowest since 1994. This is down over 7 percentage points in the last decade alone, reflecting steady diversification. Notably, central banks have been increasing holdings of “nontraditional” reserve currencies (currencies other than USD, EUR, GBP, JPY) – a combined category that surged to about 4.6% of global reserves by 2024. These include currencies like the Australian and Canadian dollars, Swiss franc, and others. However, despite China’s prominence in trade, uptake of the Chinese renminbi (RMB) as a reserve currency has actually lagged; its share is only ~2.2% and even declined since 2022 due to issues like capital controls. This indicates that much of the dollar’s lost share has gone into smaller currencies and especially into gold.

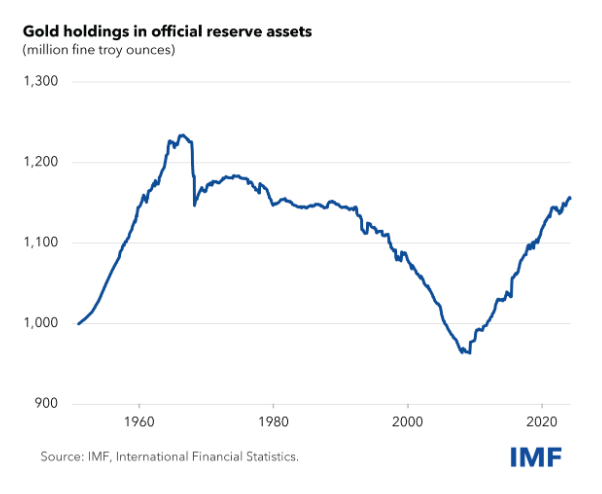

Central banks worldwide have embarked on the largest gold-buying spree in decades as a pillar of de-dollarization. Gold is seen as a neutral reserve asset (not tied to any country) and provides protection against currency and geopolitical risks. Over the past 15 years, official gold reserves globally have risen by about 6,200 tonnes (200 million troy ounces). In 2022 and 2023, central banks (notably in China, Turkey, India, Poland, and others) set record highs for gold purchases. China alone added 44 tonnes of gold in 2024, bringing its total to 2,280 tonnes, while Russia accumulated nearly 2,000 tonnes from 2005–2022 (now holding ~2,333 tonnes). Medium-sized reserve holders like Turkey (which was the largest buyer in 2022) have used gold to diversify away from dollars – in Turkey’s case, both to hedge against inflation and reduce dependence on Western currencies. This rotation into gold often comes directly at the expense of USD assets: central banks sell U.S. Treasury securities (or use dollar liquidity) to fund gold purchases. The chart below illustrates the resurgence of gold in official reserves, after a long decline in the 1990s and early 2000s, climbing back to levels last seen in the 1970s as central banks reverse earlier sales.

Figure: Central bank gold holdings in official reserves (million troy ounces). After decades of decline, gold reserves have risen sharply since 2008, reflecting diversification away from the U.S. dollar. Source: IMF IFS data.

3. Macroeconomic Factors and Domestic Financial Policy: In some cases, selling dollar reserves is driven by domestic economic needs rather than a deliberate geopolitical strategy. Several countries depleted reserves to stabilize their currencies or finances in 2024. For instance, India saw its foreign exchange reserves fall to an 8-month low of $640 billion at end-2024 as the RBI intervened to curb the rupee’s decline. Facing a record weak rupee (hitting an all-time low around ₹85.8 per USD), the RBI sold dollars heavily via state-run banks to prevent excessive volatility. In total, India’s central bank sold $15.2 billion of forex in December 2024 alone (after $20.2 billion in November), as confirmed by RBI data, marking one of its most aggressive interventions. These dollar sales were aimed at containing import-cost inflation and financial instability rather than reducing dollar exposure per se. Brazil offers a similar story: in December, the Brazilian real plunged to record lows (~R$5.30 to R$6.30 per USD) amid fiscal worries. The Central Bank of Brazil stepped in with “massive” FX operations – including spot USD sales and repo auctions – totaling over $30 billion to shore up the real. This use of reserves had the side-effect of lowering Brazil’s dollar holdings (Brazil’s U.S. Treasury stockpile dropped about $27–28 billion that month). While these actions were emergency measures, they align with a broader comfort in drawing down dollar reserves when needed, as countries feel less obliged to passively accumulate U.S. assets.

Even advanced economies have dipped into dollar reserves for market reasons. Japan in 2022 undertook large dollar-selling interventions (tens of billions) to support the yen, given the dollar’s surge. By late 2024, Japan again trimmed its U.S. Treasury holdings – by $27.3 billion in one month – partly due to changing yield differentials and possibly to reallocate funds for domestic needs. Hong Kong’s reduction of ~$11 billion in U.S. assets in 2024 reflects its currency board system, which mandates selling U.S. dollars from reserves to maintain the HKD’s peg when U.S. interest rates rose sharply.

Finally, some reserve shifts are motivated by portfolio optimization. With U.S. interest rates at their highest in decades in 2023–2024, the market value of existing U.S. Treasury holdings fell. Some central banks chose to reduce longer-duration USD securities (which were losing value) and either hold the proceeds in shorter-term instruments or in other currencies. For oil-exporting nations like Saudi Arabia, high oil prices in 2022 had boosted reserves, but by 2023–2024, the Kingdom began reallocating reserves to sovereign wealth investments and development projects. Riyadh has also shown interest in settling oil trades in alternative currencies (like the Chinese yuan) as a “small but symbolic step” toward de-dollarization. While the Saudi riyal remains pegged to the dollar, Saudi Arabia’s central bank (SAMA) has quietly explored currency diversification deals with partners like China. The drop of over $10 billion in Saudi-held U.S. securities in early 2025 may signal these shifts, though it could also fund domestic needs. In sum, some countries are actively diversifying reserves for strategic reasons, whereas others are reactively selling dollars to manage economic pressures – but both contribute to the overall reduction in global USD holdings.

Broader Impacts on Markets and the U.S. Dollar

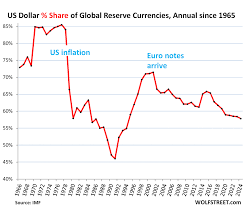

The cumulative effect of these moves is a noticeable decline in the dollar’s dominance in international reserves. The U.S. dollar now accounts for roughly 57–58% of global foreign exchange reserves, down from about 65% a decade ago and from 71% in 1999. The chart below shows the dollar’s share of global reserve currencies over time, underscoring the gradual erosion. In 2024, the USD share hit its lowest point in 30 years. This reflects both deliberate diversification and valuation effects. It’s worth noting the dollar has lost global reserve share in a “slow drip” rather than a sudden flight – a process spanning decades (for example, falling sharply in the 1970s–80s during high U.S. inflation, then stabilizing, and declining again in recent years).

Figure: U.S. dollar’s percentage share of global reserve currencies (annual, 1965–2024). The USD’s share has fallen from ~85% in the 1970s to around 58% now. Recent years show a steady decline as central banks diversify. Source: IMF COFER data.

Impact on U.S. Financial Markets: As foreign central banks and governments pull back from U.S. dollar assets, one immediate impact is on the U.S. Treasury market. Official foreign holdings of U.S. Treasuries dropped by over $120 billion in the final months of 2024. When large holders like Japan or China reduce their purchases (or actively sell), it can put upward pressure on U.S. long-term interest rates. Indeed, late 2024 saw a surge in U.S. Treasury yields to multi-year highs, and analysts partly attributed this to declining foreign demand. For example, Japan’s and China’s combined December sales (~$37 billion) coincided with a spike in yields. Over the longer term, a structural decline in official dollar holdings could mean the U.S. government must rely more on domestic and non-official investors to finance deficits, potentially at higher cost. However, this process is gradual and market-driven adjustments (like higher yields attracting other buyers) can offset short-term disruptions. The U.S. dollar’s exchange rate could also be affected. If many central banks sell dollars (and don’t reinvest in dollar assets), those dollars may be exchanged for other currencies, putting downward pressure on the USD’s value. In practice, the dollar’s value in 2024–2025 has been influenced by many factors – including Federal Reserve policy and global risk sentiment. Despite de-dollarization, the USD index remained relatively strong through 2024, thanks to aggressive Fed rate hikes making dollar assets attractive to private investors. But going forward, if reserve reallocations accelerate, we could see periods of dollar weakness, especially against currencies that become favored alternatives. Already, currencies like the euro and yen have maintained their shares (~20% and 5.8% of global reserves, respectively), and “nontraditional” currencies (Canadian, Australian dollars, etc.) collectively gained share – implying central banks are spreading bets. Some of these beneficiary currencies might appreciate gradually as reserve managers increase allocations to them.

Global Financial System Adjustments: The shift away from the dollar also encourages the development of alternative financial arrangements. We see increasing use of local currency swap lines and payment systems that bypass the dollar. For instance, BRICS countries have been exploring multi-lateral payment mechanisms in local currencies. China has established yuan clearing banks and swap lines with dozens of countries, enabling partners like Argentina or Pakistan to access RMB for trade instead of drawing down dollar reserves. While these systems are still relatively small-scale, they reduce some demand for dollars at the margins. Additionally, new digital payment technologies (such as central bank digital currencies and other tokenized assets) could, in the future, lower the need for holding large dollar reserves for liquidity. The BIS and other institutions are piloting cross-border CBDC platforms (e.g., mBridge with China and Gulf states). If successful, such innovations might allow countries to transact seamlessly in different currencies, weakening the dollar’s intermediary role over time.

Risks and Stability: A concern is that rapid dollar reserve sales could destabilize markets. So far, central banks have been careful – Russia’s NWF conversion was done internally to avoid market shock, and China’s reserve shifts have been gradual and transparent (“routine diversification”). Most countries are not dumping dollars in a fire sale; they are simply rebalancing at the edges. Moreover, the dollar still enjoys network advantages – it remains the preferred invoicing currency for ~54% of global trade (as of 2022) and is involved in 88% of FX trades. This entrenched usage means reserve managers can’t reduce dollars too far without risking liquidity issues. Even BRICS officials acknowledge the dollar won’t be replaced overnight. In fact, despite political rhetoric, Brazil and others concede there’s “no chance” a new BRICS currency will soon supplant the dollar in trade. The petrodollar system, while loosening, is still largely intact – most oil sales (even by Russia and Middle East) are still in USD, sustaining recycling of petro-dollars into dollar assets. Thus, the pace of change is evolutionary. An expert panel of economists at the 2025 World Economic Forum summed it up well: U.S. dollar primacy is expected to continue for the foreseeable future, but with gradual diversification underway. In other words, we are likely moving toward a more multipolar reserve currency system where the dollar shares space with the euro, yen, yuan, and gold – rather than a sudden dollar collapse.

Conclusion and Outlook

The year 2025 finds the global reserve landscape in flux. Countries across Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East have shown an unprecedented appetite to trim their U.S. dollar reserves, whether to mitigate geopolitical risk, defend their currencies, or seek better returns through diversification. Official data and interventions reveal sizable dollar sales by major holders like Japan and China, proactive de-dollarization in Russia and parts of the BRICS, and opportunistic reserve use by India, Brazil, and others to stabilize economies. As a result, the dollar’s share in central bank coffers has slid to a generational low, and the trend is poised to continue.

From a historical perspective, this shift is significant – it marks the dollar’s slow retreat from the **85% dominance it enjoyed in the 1970s to under 58% today. Yet it is also clear that the U.S. dollar remains the single most important currency in the world financial system by far. Even after selling billions in Treasuries, most countries still hold the bulk of their reserves in USD assets, and global trade and debt markets are still heavily dollar-centric. The changes occurring now – more gold, more yuan or euro, more local currency deals – amount to a diversification hedge rather than a wholesale abandonment of the greenback.

Going forward, we can expect:

Continued Reserve Diversification: Central banks will likely keep increasing allocations to gold and a mix of secondary currencies. The dollar’s share could erode further (analysts forecast another 10% drop in the next decade). No single replacement will take over – instead a “wide array of currencies” will benefit, from the euro and yen to the yuan and others. This means reserve managers will be more balanced and less exposed to any one currency’s fate.

Dollar Remains Indispensable (For Now): In the short to medium term, the dollar’s fundamental role is secure. Its status is underpinned by the size and stability of the U.S. economy, deep U.S. financial markets, and the lack of a ready alternative that matches its liquidity. As the Davos panel noted, the world has a “love-hate relationship” with the U.S. dollar – many resent its dominance but still rely on it. The U.S. dollar will likely remain the principal reserve and safe-haven currency until global trust and infrastructure build up around others.

Implications for the U.S.: American policymakers face a delicate balance. On one hand, gradual de-dollarization is a manageable trend. On the other, it signals a slow decline in the “free financing” the U.S. enjoys from foreign reserve accumulation. If countries buy fewer Treasuries, the U.S. may ultimately pay more to borrow, and the Treasury might need to entice a broader base of investors. The U.S. administration must also be mindful that excessive use of sanctions or threats (such as recent tariff warnings against dedollarization by former President Trump) could accelerate moves away from the dollar. Maintaining confidence in U.S. institutions and avoiding default or instability is key to preserving the dollar’s appeal.

Global Collaboration: As reserve holdings spread out, international coordination could become more complex. We may see more bilateral and regional agreements (like swap lines and local currency pacts) that bypass traditional dollar-based systems. Forums like the BRICS, ASEAN, or Gulf Cooperation Council will likely continue discussing monetary cooperation. This incremental decoupling from the dollar in some transactions could reduce global demand for U.S. dollars at the margin, but also requires new mechanisms to manage exchange rate volatility between emerging currencies. Greater collaboration on financial technology (for instance, linking digital currency platforms) might emerge to support this multi-currency ecosystem.

In conclusion, 2025 has so far underscored a pivotal shift: a world where central banks are no longer unquestioningly accumulating U.S. dollars, but are actively rebalancing portfolios. Major countries have sold tens of billions in U.S. dollar reserves, reflecting a mix of strategic intent and tactical necessity. The U.S. dollar’s dominance, while dented, is not defeated – it continues to be the cornerstone of global reserves, even as its share slowly shrinks. For policymakers and investors, the key is to watch not just which countries are selling dollar reserves, but why. Those underlying reasons – from geopolitical realignments to economic self-defense – will shape the trajectory of the dollar in the international system. Gradual de-dollarization is underway, but the end of dollar dominance, if it ever comes, remains a long way off. In the meantime, the world is adapting to a new reality: the U.S. dollar is first among many rather than the only game in town, as countries recalibrate their trust and holdings in the greenback.

Sources:

Reuters, “Foreign holdings of US Treasuries fall in December” (Feb 2025) – data on Japan, China sales.

Global Times, “China cuts holdings of US Treasury bonds to $759 billion” (Feb 2025) – China’s 2024 declines and diversification to gold.

U.S. Treasury Department TIC Data – Major foreign holders of Treasuries (Jan 2025 update).

Reuters, “Brazil’s gross debt… aided by foreign reserves sale” (Jan 2025) – Brazil’s $30B intervention in Dec 2024.

Times of India, “RBI net sold over $15 billion forex in December” (Feb 2025) – India’s RBI interventions in Nov–Dec 2024.

Wolf Street (Wolf Richter), “Status of US Dollar as Global Reserve Currency” (Mar 2025) – global reserve currency shares and trends.

OMFIF (Gary Smith), “Which currencies will benefit from dollar erosion?” (Jan 2025) – on weaponization of dollar and projected share decline.

Atlantic Council (Hung Tran), “Is the end of the petrodollar near?” (June 2024) – on Saudi diversification steps.

World Economic Forum, “Why the US dollar will be indispensable… until it’s not” (Jan 2025) – economists’ panel on dollar’s future.

Moscow Times, “Russia to Ditch Dollar From $185 Bln Reserve Fund” (June 2021) – Russia’s removal of $41B in USD assets.